If your startup is just getting off the ground, the simplest, fastest, least expensive way to raise money is by selling SAFEs or convertible notes.

Referred to collectively as “convertible instruments,” issuing SAFEs and convertible notes to investors lets you put off a 409a valuation, while still raising funds from investors.

While SAFEs and convertible notes both convert to equity, selling them is not the same as selling shares in your company. Think of them as IOUs, guaranteeing early investors preferred shares later on.

So, what happens when the axe falls, and it’s time to turn those SAFEs and convertible notes into equity? First, a brief overview of how the two financial instruments work, and how they differ from one another. Then, we’ll get into how they convert into equity—or don’t—based on how your company performs.

The differences between SAFEs and convertible notes

First came the convertible note. Then came the SAFE.

Until 2013, startups could only raise money with convertible instruments by selling investors convertible notes. Then Y Combinator invented the SAFE: a streamlined version of the convertible note.

It’s faster and cheaper (in terms of legal fees) to prepare a SAFE than to prepare a convertible note, and SAFEs have become the standard for early stage fundraising in Silicon Valley. Using Capbase, you can issue both SAFEs and convertible notes at no additional cost.

Outside of the Valley, and in industries such as crypto, medical research, and aeronautics, investors may prefer convertible notes. While SAFEs are fast and easy to use, they offer less flexibility than convertible notes.

The following is just a quick overview of the differences between the two products. Our guide to the key differences between SAFEs and convertible notes takes a deeper dive.

What you need to know about convertible notes

A convertible note acts like a bond—meaning, it’s a form of debt. When an investor pays you for a convertible note, they’re lending you money. In exchange, they can collect interest on the value of the note.

Interest on convertible notes ranges from 2% to 8%, but it’s typically 5% or 6%.

Every convertible note has a maturity date, typically set at 18 – 24 months after the note is purchased. When the maturity date is reached, one of three things happens:

Your startup must pay back the investor the value of the note, plus interest.

You negotiate a new maturity date for the note. (This is the most common outcome.)

The value of the note is converted into preferred shares.

Most startups, at this stage of fundraising, don’t have the cash to pay off the value of a convertible note, plus interest. (In many cases, doing so could bankrupt them.)

You may negotiate a new maturity date with the investor. But the most desirable outcome, for investors, is that the value of the note converts to preferred shares, which the investor receives. Ideally, this happens before the maturity date, either through a financing round or the acquisition of the company.

In the event of acquisition, if the founders of the company that originally issued the notes have enough cash, they may pay out the value of those notes (including accrued interest), effectively buying them back from their holders. This allows them to secure control of equity that would otherwise end up in the hands of investors.

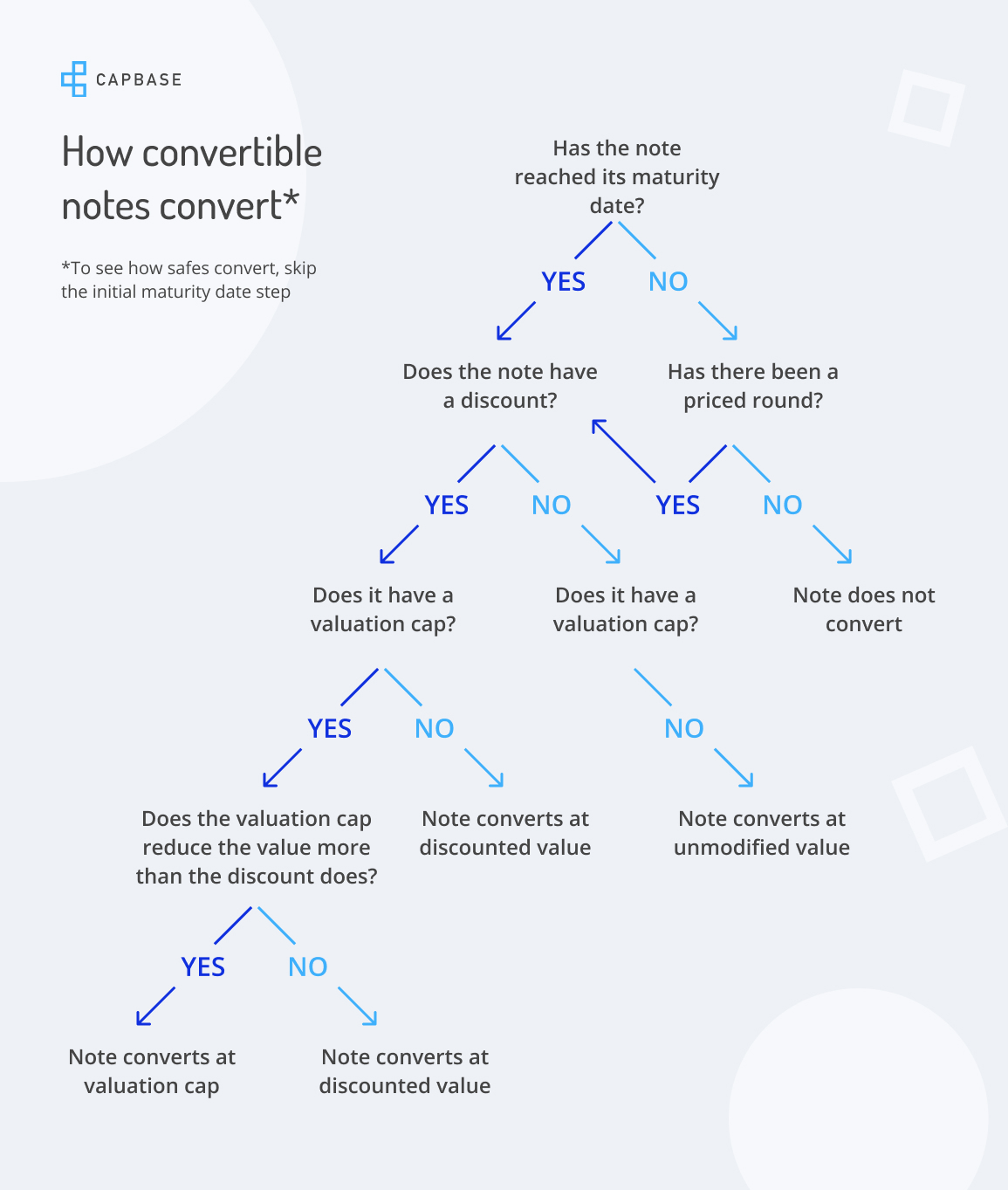

How a convertible note converts

If your startup holds a funding round before a convertible note reaches maturity, the note is triggered into converting into equity.

On a very basic level, if an investor holds a convertible note for $500,000, when it’s triggered, they receive $500,000 worth of preferred shares. But this conversion is affected by two factors, either or both of which are listed in the terms of the note: the discount rate, and the valuation cap.

The discount rate is like a reward the investor receives for investing money during a startup’s early days, when risk is high. When the note converts, it allows them to purchase shares at—you guessed it—a discounted rate.

Discount rates are typically 10% – 20% of the total value of converted equity. The discount rate allows the investor to acquire more shares—and a bigger piece of the company—for the cost of their investment.

The valuation cap sets a limit on how highly shares can be valued for the sake of conversion. If during a funding round a company is valued at $10 million, but the convertible note you hold has a valuation cap of $5 million, you will acquire shares at the price they would be at a $5 million valuation—effectively half price.

A convertible note may include, as part of its terms, either a discount rate or a valuation cap, or both. In the event the note features both, the investor acquires shares at the lowest rate—which is to say, they get the biggest possible bang for their buck.

Even if the valuation cap is higher than or equal to the valuation of the company during its funding round, if the note includes a discount rate, the discount rate still has an effect. For instance, if a note has a $10 million valuation cap and a 20% discount rate, if the company is valued at $10 million during the funding round, the note holder will acquire shares at a 20% discount.

Convertible notes can either be pre-money or post-money, both of which are covered in detail below.

What you need to know about SAFEs

SAFEs are like convertible notes, except they don’t accrue interest, and they don’t have maturity dates. They aren’t a form of debt. Rather than a bond, a SAFE is a form of warrant, signed by a startup and given to investors, saying, “In exchange for X dollars, I will give you X dollars worth of preferred shares once certain conditions are met.”

The “certain conditions” are the SAFE’s trigger. Since SAFEs don’t have maturity dates, that trigger is a priced round. How a SAFE converts

How a SAFE converts

Much like a convertible note, a SAFE can include either a discount rate, a valuation cap, or both. These operate in a similar fashion, allowing the SAFE holder to acquire more equity than they would with a direct version based on the company’s value at the time of the priced round.

The way a SAFE converts depends on whether it is a pre-money SAFE or a post-money SAFE.

Early critics of SAFEs noted that it was difficult for founders to predict how much of their companies would be acquired by SAFE holders during priced rounds. In response, Y Combinator created a new version of the SAFE in 2018, which they called the “post-money SAFE.” The original version of the SAFE became the “pre-money SAFE.”

When a SAFE converts, the conversion price is calculated by dividing the valuation cap by the company's capitalization (the total number of shares and options).

Valuation cap / Capitalization = Conversion price

With a pre-money SAFE, the company capitalization consists of all its shares and options, not including shares issued when the SAFE converts.

With a post-money SAFE, the company capitalization includes shares issued when the SAFE converts.

So long as every other part of the equation is factored on a pre- or post-money basis, the outcome should be the same. Meaning

Pre-money valuation cap / Pre-money capitalization

Will result in the same conversion price as

Post-money valuation cap / Post-money capitalization

So, why bother choosing one type of SAFE over another? What’s the difference?

Predictability. For instance, a pre-money SAFE offers insurance to investors in the event the company decides to extend its financing round, ensuring that, during conversion, the SAFE’s valuation cap takes into account the extended financing, rather than sticking to a higher (post-money) price.

Employee stock option pools (ESOPs) play a role as well. Pre-money SAFEs include unissued stock in ESOPs, as well as any increases to the ESOP that occur during financing; those increases, for the time being, are a giant question mark. Post-money SAFEs include the option pool, but typically exclude any increases—removing that unknown quantity.

At the end of the day, a post-money SAFE tends to benefit the holder, rather than the issuer. A pre-money SAFE dilutes the SAFE holder’s shares, due to stock being issued during conversion. With a post-money SAFE, that dilution is mostly borne by existing shareholders—usually founders and employees.

SAFEs can be difficult to predict—at the very least, it takes some number crunching to map out different funding round scenarios, and what they mean for your ownership of your startup.

Luckily, if you’re using Capbase, you can issue SAFEs and see in advance how much ownership they entitle the holder to. Book a demo if you’d like to see, in real time, how this looks for your business.

Selling SAFEs and convertible notes with different terms

Raising capital with SAFEs and/or convertible notes, you may find yourself issuing different notes with both different values and different terms.

Example:

- SAFE 1 is worth $400,000, with a valuation cap of $5 million and a 10% discount.

- SAFE 2 is worth $600,000, with a valuation cap of $8 million and a 20% discount.

- SAFE 3 is worth $1 million, with a $12 million valuation cap and no discount.

In this case, during your first funding round, your Series A documents will include three subseries: Series A1, Series A2, and Series A3.

Each of these shareholders will pay a different price for their respective subseries of shares—their differing valuation caps and discounts make sure of this.

If we include convertible notes in this example, it will become much more complicated—convertible notes introduce the complexity of maturity dates, and they’re more flexible overall than SAFEs. You can expect more differences from convertible note to convertible note than you can expect from SAFE to SAFE.

The math for calculating how these different subseries convert, and how much of your company each SAFE or instrument holder will own, is complex. If you use Capbase, the calculations are handled for you. Your cap table is automatically updated as changes occur.

A final note: some convertible notes and SAFEs include most favored nation (MFN) clauses. Under the terms of such a clause, if the holder buys the SAFE or note, and then you issue more SAFEs or notes with better terms, they reserve the right to adopt those terms. (Pre-money SAFEs include an MFN clause as a default; post-money SAFEs do not.)

In the event a SAFE or a convertible note doesn’t include either a discount or a valuation cap, they almost certainly include an MFN, allowing the holder to adopt the terms of future investors.

SAFEs and convertible notes when your company exits before a priced round

When a startup makes it to a funding round, and continues to grow in value afterwards through subsequent rounds or being purchased, individuals holding SAFEs and convertible notes are happy. Their risk-taking has paid off, and they now have valuable shares in hand.

This doesn’t happen in the event of a pre-round exit. In that case, your company is purchased or fails before you hold a priced round.

As a result, your company must pay back SAFE and convertible note holders the value of the product they purchased, dollar for dollar. (Since you’re incorporated, it’s your company that is on the line for the debt, not you personally.)

Since SAFEs are more like equity tools than debt, they get the second order of preference after convertible notes, which are paid out before them.

Summary

- SAFEs are a newer, faster, non-debt version of convertible notes, which follow a standard format set by Y Combinator

- Conversion is triggered by funding round or sale of company (both SAFEs and convertible notes) or maturity date (convertible notes only)

- How a SAFE or convertible note converts is affected by its discount rate (typically 10% – 20% off its converted equity value) or valuation cap (maximum value at which shares are priced)

- During a liquidity event, the corporation must pay back the purchase price of convertible notes and SAFEs to investors

Keeping an up to date cap table ensures you’re tracking all ownership in your company, as well as SAFEs and convertible notes. Not familiar with managing a cap table? Our ultimate guide to cap tables for startup founders will get you started.

by

by

by

by