Messing up your cap table is one of the earliest, easiest ways to create problems for your startup.

Venture capitalists, angels, and other investors don’t want to back a company with cap table issues. The reasons why are myriad—but, bottom line: messy cap tables create risks smart investors want to avoid.

And depending on how much damage you’ve done, the task of cleaning up a dirty cap table ranges from difficult to near impossible.

Some good news: the leading cause of cap table trouble is ignorance. Once you understand the most common cap table mistakes and their consequences, you’re on track to raise funds intelligently, without creating problems later on.

How do cap tables work?

Our ultimate guide to cap tables for startup founders gives you a full crash course. But here’s the tl;dr.

Your cap table tells you:

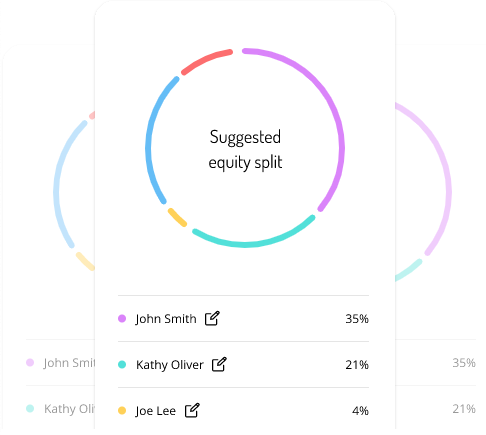

- Who owns stock in your company

- Who owns convertible notes and SAFEs that will become stock

- How much of the company everyone owns

- What types of stock they hold

- Which stock has vested, and which hasn’t

Your cap table may take the form of a spreadsheet. (This is where many founders go wrong, opting for time-consuming Excel templates instead of a comprehensive cap table solution.)

More broadly, your cap table also includes the contracts, stock certificates, and other items in your document room that determine who owns what. (When you use Capbase, those documents automatically sync with your cap table, so both are always up to date.)

So, when we talk about your cap table, we’re talking about how ownership in your company is structured.

Your cap table starts off simply, with one to three founders holding shares in the company. Some shares are also set aside as competition for future hires—board members, senior members of the management team.

As you issue equity to new team members and investors, your cap table becomes more complex; stock value is diluted, new types of shares (ie. preferred stock) come into play, and it can become more difficult to keep track of who owns what.

That’s when the problems start.

1. Giving advisors too much equity

So, after crawling your network to its outermost friend-of-a-friend-of fringes, you’ve managed to sit down with the superstar advisor of your dreams. Not only that, they love your product, your team, and your je ne sais quoi, and they’d love to sit on your board. All they need is a little equity—say, a mere 15% of your company.

But wait: before you start slicing up the pie, take a moment to make sure you understand two major problems.

First of all, a double digit equity stake is far above market for any advisor. This person isn’t a founder, and they aren’t helping manage any personnel. They’re a mentor. And no matter how well-known and respected they are in our niche, they don’t deserve as big a stake in your company as someone who has thrown themselves 100% into making your business succeed.

In fact, they’re likely throwing far less than 100% into your business. That’s the second problem. As a star advisor, they’re in high demand—so, how many other startups are they advising? What is their stake in the success of other businesses, or in their own venture?

If you’re the only founder they’re advising, it’s understandable how a 10% or even a 15% stake may seem reasonable, at first. But even then, how valuable is the advice you’re receiving? Is it worth one tenth of your company?

Ultimately, it isn’t up to you to decide what a celebrity advisor deserves to receive. It’s up to investors. To most VCs, an advisor with an oversized cut of the cap table is a warning sign.

For starters, it shows that you don’t know what you’re doing, or that you’re following bad advice—since double digits are so drastically out of step with what most advisors receive.

Most of all, though, it suggests troubles to come. Having 10% or 15% of your equity in the hands of someone who doesn’t have a direct stake in your company can create hassles when it’s time for shareholders to vote. It can also lead to dead equity—someone who has moved on from your company, but ties up a significant portion of its value in shares they hold.

2. Founders without vesting schedules (dead equity)

When founders’ shares don’t have vesting schedules, you run the risk of dead equity on your cap table.

True to its name, dead equity is dead weight. Dead equity is stock in your company, held by someone who no longer has a vested interest in said company. That equity doesn’t do any work for you—it isn’t acting as a motivation for someone to help you succeed. And when you need to reach shareholder consensus, tracking down someone who holds dead equity can throw a wrench in the works.

Plus, it makes investors anxious; they’re not sure how a dead equity holder will react to outside investments, and whether they’ll create any trouble.

One major cause of dead equity: co-founders who jump ship, taking their shares with them. Even if you manage to part on good terms, having an individual who does not participate in your business walking around with double digit equity is a bad look.

The easiest way to avoid this problem is a vesting schedule. The exact details are up to you, but many founders opt for a 48 month vesting schedule with a 12 month cliff. Meaning, founders have to stay onboard at least one year after incorporation before they can get any equity; it will take a full four years for them to get all of it.

If someone has invested considerable sweat equity before founder shares are available for purchase—for instance, in developing your product—you may choose to skip the vesting period and let them get their hands on stock right away. Fair enough—but be sure to weigh the risks.

In the event you need to clean up your cap table and get rid of dead equity, your only option is to buy back the stock in question. In that case, convincing someone to sell you stock at a price you can afford may be tough. In some situations, founders can convince dead equity holders to return stock because, if they don’t, the company won’t manage to raise a round of funding—since dead equity is such a turn-off for investors.

In that case, you’ll be convincing them to go from double-digit stock holdings to single-digit, merely to insure the stock retains some value (ie. your company doesn’t fold due to lack of funding).

3. Selling too much, too soon

With stories of massive funding rounds packing headlines, it can be hard not to get obsessed with raising as much money as possible. If you let this temptation take over, you could end up in hot water.

For starters, when your company is still young and your product in its infancy, you don’t have much leverage; there’s no data you can bring to a meeting with an investor to prove that you’re positioned to grab a piece of the market and take off.

So, when you start negotiating with investors over large sums, you’re more likely to be following their terms, rather than setting your own. Too often, that means giving up such a large share of your company that you and your co-founders lose control early on.

Beyond the risk of losing control of your business, aiming high during early fundraising rounds can cause other problems. For instance, a high valuation early on may come back to bite you. If you don’t scale as quickly as expected, or run into hiccups along the way, you could find yourself trying to raise another round at a lower valuation than before.

4. Failing to track incentive and non-qualified stock options (ISOs and NSOs)

Offering stock options to new employees helps you hire top talent early in the game, but it’s important you’re clear on the differences in how incentive and non-qualified stock options are taxed.

Broadly, ISOs are taxed when they’re sold, not when they’re exercised. At that point, they’re taxed at the capital gains tax rate.

For NSOs, the stockholder is taxed on the spread (the difference) between the grant price and the exercise price. That tax is charged as part of their regular income, and it’s triggered when the option is exercised. Not only does the stockholder need to withhold income tax at the time of exercise, but they must also set aside payroll taxes (Medicare and Social Security), which total 7.65%.

Clearly, for the stockholder, ISOs are preferable, because of how they are taxed. But ISOs have limits. You can be taxed on a maximum of $100,000 in ISOs for the financial year—everything over that amount is taxed as NSOs.

This is often referred to as the “$100k rule,” and it’s the reason for ISO/NSO splits—startups structuring their options grants so no single employee’s vested stock is equivalent or greater than $100k.

Further complicating matters, your company is able to file tax deductions for employee NSOs that vest.

We won’t take a deep dive into the technicalities surrounding ISO/NSO splits. Suffice it to say, if you mix up NSOs and ISOs, or fail to differentiate between the two, you can land yourself in a pile of tax ugliness. When founders make this mistake, it takes the help of a skilled accountant to clean up the mess.

5. Overdilution during high resolution fundraising

High resolution fundraising—offering different terms for convertible notes and SAFEs, with the aim of encouraging early and particularly helpful investors to buy in—offers a lot of flexibility during seed and pre-seed rounds.

But the potentially vast number of different valuation cap and discount combinations, plus the differences in pre- and post-money valuation, can create a mess of numbers to keep track of.

If you aren’t using advanced cap table software, like Capbase, you run the risk of miscalculating how much your own shares will be diluted. Meaning, when the dust settles, you may find yourself owning less of your company than you anticipated.

The easiest way to prevent this problem is to make sure you have a solid cap table solution in place, that allows you to see in real time how differing terms will affect ownership of your company.

The biggest problems I’ve seen with startup cap tables usually have to do with stacking or rolling SAFEs during an initial fundraise. My advice: be careful, and make sure you have a model for tracking your SAFEs. I’ve seen founders who did a bad job of tracking them. When it was time for a priced round, they were surprised at how much of their company they’d given away!

– Charley Ma, GM of Fintech at Alloy, angel investor

BONUS MISTAKE: Out-of-sync legal documents

One more major investor turnoff: legal agreements that don’t match up with your cap table.

These can cause major problems during due diligence, even leading to lawsuits.

The primary cause is poor cap table reporting. If you’re managing your cap table with spreadsheets or a cap table app that’s weak on the features front, you have to manually make changes to the table in accordance with new legal documents and changes to existing one. That opens up vast potential for human error—minor mistakes that cost you a lot later on.

Capbase automatically syncs all your documentation with your cap table. So you don’t have to worry about a mistake rearing its ugly head in the middle of due diligence.

Want to take Capbase for a spin? Book a call today.

TL;DR

- Making cap table mistakes now can create major problems later on—including turning off investors

- Advisors typically get equity in the single digits—any higher, and you risk turning off investors due to the risk of dead equity

- When founders’ equity doesn’t have a vesting schedule, there’s a greater risk of dead equity

- ISOs and NSOs are different—make sure to differentiate, or you’ll be in danger of making tax errors

- Keep track of how your shares dilute during fundraising, or you could lose control of your company

by

by

by

by