How Do Venture Capitalists Make Money?

by James Hottensen • 7 min readpublished April 22, 2021 • updated December 4, 2023

by James Hottensen • 7 min readpublished April 22, 2021 • updated December 4, 2023

Like everybody else, VC's have bosses: LP's.

Venture Capitalists have KPI's and goals they have to hit in order to please their LP's, just like startups have to meet KPI's and goals to satisfy their investors.

It's important for every startup founder to have as much context as possible about how a VC fund works and how they measure their own success to maximize the chances of securing investment.

Before getting into the mechanics of how a modern VC fund works, let's rexplore the origins of venture capital and how the business got started, way back in the 18th century.

The Origins of Venture Capital

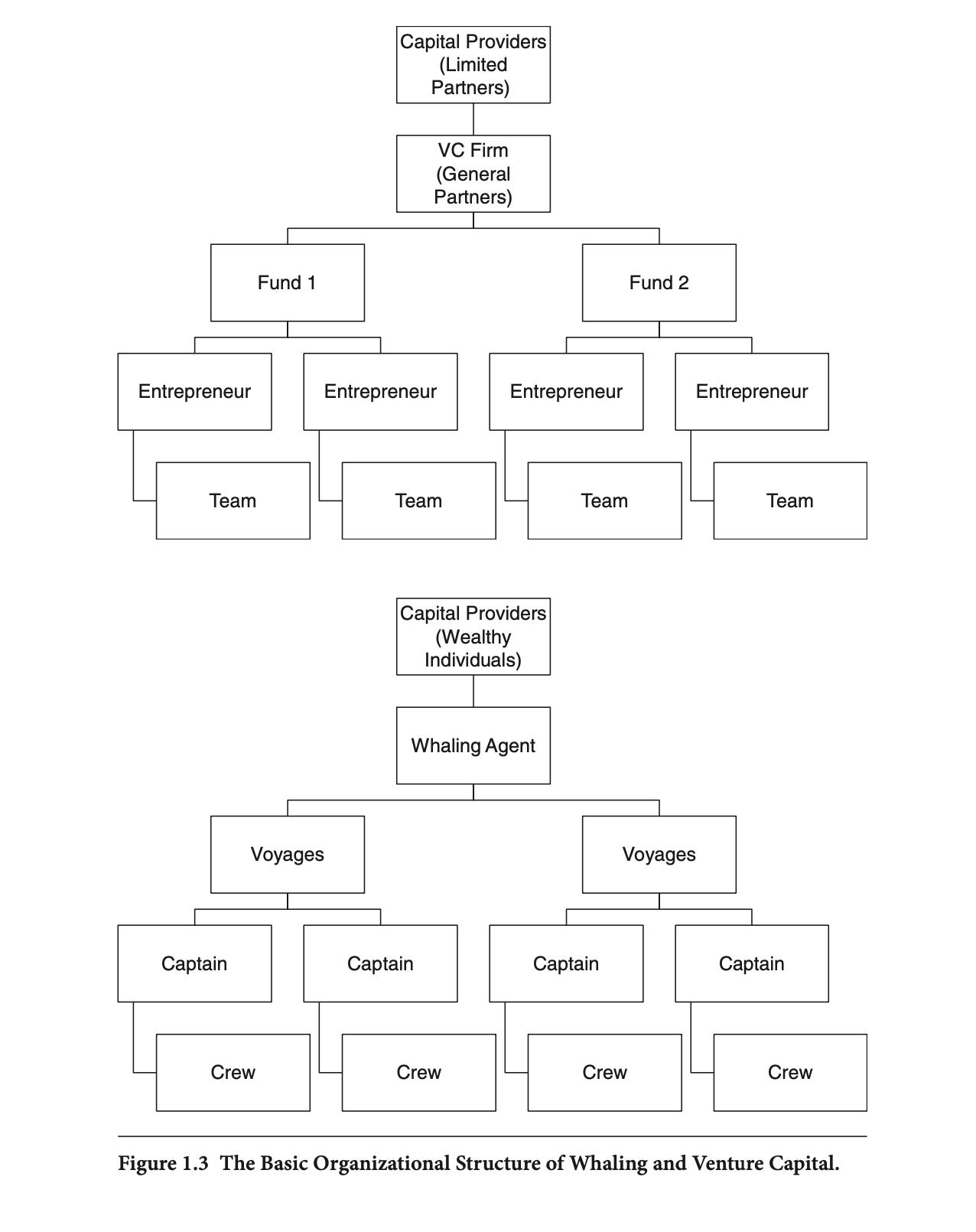

The origin story of “Venture Capital” as an asset class can be tied back to one of the oldest industries on the planet: whaling. That connection may not make sense intuitively, but they both share a common architecture: a capital provider and a principal investor.

In the whaling industry, the capital provider would be wealthy individuals who have enough excess capital to invest into a risky venture like a whaling expedition. These individuals, think of them as the LP’s, would give a whaling agent (VC firm) capital to finance the trip and hopefully bring back a whale. A successful expedition was rare, much like a VC investment today, but had the potential for outsized returns. In fact, the return profile on a whaling expedition was very similar to that of a VC investment today. In both, you have a capital provider giving money to an agent, who is trusted with the capital to run an expedition in pursuit of financial returns.

Think of each VC’s individual fund as a voyage, and the companies that they invest in as the ship, with the captain being the founder and his employees as the crew. Tom Nichols provides a helpful diagram to illustrate this structure in his book VC: An American History

In this context, the business model of a VC is straightforward. But the business model has evolved considerably since the whaling days, and there are new ways VC’s make money and are measured. What hasn’t evolved is the need for these funds and expeditions to produce considerably higher rates of return than a typical investment for the fund to make money.

VC Glossary of Terms

Before getting into the nitty-gritty, it’s important to understand a few basic terms:

- AUM: Assets Under Management: the total $ amount that the fund has raised and deploys into investments

- LP: limited partners aka the investors in the fund. For a large fund these are entities like Pension Funds for Unions/teachers or sovereign wealth funds of countries, or Hedge Funds/high net worth individuals. To go back in time, these are the high net worth individuals who financed the whaling expeditions!

- Capital calls: LP’s don’t invest all of the money at once. It is ‘called’ by the VC fund periodically or over a standard period of time. LP’s commit a certain amount of money, but the actual cash reserves of the fund vary as they make additional capital calls over time.

- Distributions: the money paid back to investors after an acquisition or exit

- Exit/”Liquidity Events”: An instance where a company is bought by another company or fund. Usually this is a combination of cash and stock, so the investors would receive a proportional amount to the money invested

- Ownership %: the percentage of the company that the fund controls

- “2 and 20”: 2% fee on AUM, 20% on profits. More on that later.

- “Return the fund”: When an individual investment exits for an amount that creates enough distribution to LP’s to make them whole

- IRR: Internal rate of return. This is measured by ‘marking up’ an investment based on its most recent valuation. If Capbase Capital were to invest in a company at a $5mm valuation in a SAFE, and it went out and raised a new round of capital 12 months later at $60 million, it would be marked at 12x, or 1,110% IRR. That is not likely to repeat over time, and most investors shoot for 30% IRR across a fund, knowing that most will go to 0. You can argue that IRR is not a very rigorous calculation because it is based on valuation, which is itself a subjective measure of the company.

- TVPI: Total Value to Paid in Capital. Total value of the fund’s assets divided by the total value of capital ‘called’ by fund. Quick example, let’s say a VC has a $100M fund. If they have called 50% of the capital ($50M), returned $20M to their investors from exits, and the remaining portfolio is worth $55M, then TVPI = ($20 + $55) / $50 = 1.5

- DPI: Distributions to Paid in Capital. Formula is: How much money VC’s have sent back to LP’s divided by total $ they have paid into the fund. The denominator is the same for both the TVPI and the DPI, but the DPI shows how much money the fund has actually returned to its investors, not the marked up value the fund has determined. At the end of the day, DPI is the most important thing for an LP.

- Carried interest: Fee funds charge to manage the capital (both on AUM and on profits)

2 and 20

“2 and 20” is an easy to remember term that summarizes the core business model of a VC fund: 2% management fee and 20% carried interest.

The management fee is what is used to finance day to day operations, and the carried interest is the performance bonus paid to the investors. Another way to think about carried interest is that it is a fee charged as a percentage of the profit the fund makes on an investment. From the LP’s perspective, their returns are measured “net of fees”. To break it out into a simple equation: Performance = ending value of LP investment - (initial capital invested + carried interest + management fees).

The Management fee is typically 2% of the total AUM, or Assets Under Management. If you are running a $100mm fund, you will have $2mm to run the business. That will cover office space, employee salary, professional services like auditors and accountants, and anything that can be used to raise the profile of the business. Typically, the management fee stays around 2% regardless of the size of the fund.

The carried interest, the “20” differs depending on the fund, but is usually never below 10% and never above 30%. The funds with a more established track record can charge a 30% carried interest fee because it is ostensibly a less risky investment than a first-time fund manager. So what does this look like in practice?

Let’s say this $100mm fund has a $1mm investment into Iris, a cyber security company. The fund owns and retains 5% of the business at a $10mm valuation, and after 5 years, Iris sells to AON for $100mm. The investment is now 10x it’s initial value, and the fund is distributed $10mm. Of that $10mm, the fund takes 20% of the profits ($2mm), and the rest ($8mm) goes back to the LP’s. That $2mm is returned to the employees at the firm who control the “economics” of the fund, or an ownership %. That is typically paid to the Partners, but many funds will pay a small % of the profits to the Associate or Principal who sourced the investment. This is how VC’s incentivize junior employees to source deals.

The Babe Ruth Effect

If every investment was as clean as Iris, then VC would not be as risky as it is. The reality is that most investments in a VC fund don’t produce any returns to its LP’s at all. In fact, the median fund has 70% of its investments produce $0 for its LP’s.

But, to bring it back to whale hunting, if 7 out of 10 voyages fail, it’s logical those 3 voyages would have to be huge successes to make up for the history of failure. This is phenomenon is commonly referred to as a “Power-Law” distribution. Chris DIxon of A16z wrote a very well-known blog post among VC's in 2015 called “The Babe Ruth Effect in Venture Capital” where he posited that

“It isn't surprising that the bad funds lose money a lot, or that the good funds lose money less often than the bad funds. What is interesting and perhaps surprising is that the great funds lose money more often than good funds do. The best VCs funds truly do exemplify the Babe Ruth effect: they swing hard, and either hit big or miss big. You can't have grand slams without a lot of strikeouts.”

To break this down further: while Iris was a *good* investment by almost all stretches of the imagination, it is not good enough to return a fund on its own. Remember that if you raised $100mm, you need to return at least $100mm back to the LP base. Iris returned $8mm back, so the VC still has $92mm left.

But what if in addition to Iris, the VC fund invested in Harbor, a data analytics company. Let’s assume they invested a similar stage and price, $1mm deployed to control 10% of the company, but Harbor went on to IPO at a $1billion valuation. The VC fund’s investment would be valued at ~$100 million. That investment alone would pay back all of the LP’s and make the entire fund worth it. If the mandate of the fund was to write 100 $1mm checks, the fund could have 99 out of 100 investments go to 0, and they would still be fulfilling their fiduciary duties, on paper.

Measuring the performance of a venture fund

We have covered what happens when a fund invests in a company and how the profits are distributed when there is an exit, but what happens in between those events? The reality is that most of the ‘progress’ a company makes exists ‘on paper’ and the monetary value isn’t actualized until a company is sold or goes public.

One of the principal differences between a VC-backed company and a typical cash-flow positive business is the lack of profitability and liquidity. In a typical “main street” business like a laundromat, there is an expected time frame when the business will become profitable. Once that point comes, the owner of the business can start retaining the profits for herself and to the investors of the business venture on a yearly or quarterly basis.

VC-backed businesses don’t work that way. In a VC-backed business, they are operated under a fundraising milestone based framework: if the business can get to X revenues (likely still not profitable), there will be funding available to get it to Y valuation. The valuation is what the investor thinks the company can reasonably achieve, but very often, that valuation is a combination of analysis and qualitative reasoning. So as the company grows and it’s value accrues at each subsequent fundraising round, the company is ‘marked’ on the VC’s books as such. But that does not guarantee that the company will retain or surpass that valuation.

To illustrate that, let’s imagine a third company, Lane. The VC fund invested in Lane at a $10mm valuation like Iris and Harbor, and Lane quickly shot up to a $200mm valuation.

The VC fund has it’s investment in Lane marked at $20mm, because they control 10% of the company. Let’s also assume that the VC fund has multiple investments like Lane that have raised multiple rounds at increasing valuations. These investments, on paper, are worth x% higher than what the fund paid for. Measuring the fund by the ‘on paper’ value of each investment is called TVPI: total value of paid in capital.

But Lane has a tough 2022, and it has to sell the business at a lower valuation than it’s previous round for $80mm. This investment is now worth substantially less than Iris, even though at one point, Lane was twice the valuation of Iris.

This situation is not ideal but common enough to take note of: a fund’s TVPI is not guaranteed and is subject to change until the money is distributed to its LP’s. That is why some funds refer to DPI to measure a fund’s success: distributions paid in capital.

Newer funds tend to use TVPI to advertise their returns, while older funds who have a longer track record can point to DPI as a way to communicate their track record.

In both, it’s important to realize that funds are in the fundraising milestone business, too: just as a startup can derive its market momentum from a lifted valuation, the VC benefits in a similar fashion but is expressed by an increased TVPI.

Financial models and ownership percentage in venture investing

Why do some venture funds target a 1, 5, or 10% ownership stake in startups? Why do some pre-seed/seed investors write the same size check into companies, irrespective of ownership percentage?

Not all funds have the same philosophy around what ownership percentage to target. This is usually driven by the fund’s size: Andresssen Horowitz or a high AUM VC fund will simply not write a small check of $50,000, just as a new, smaller VC fund may not be able to put in $1,000,000 into a Seed Round. Why?

Think about each check as a % of the AUM of the fund, and then think about ownership percentage.

A small micro-fund of $10,000,000 may want to have the ability to invest their ‘pro-rata’ amount into a startup, given their position as an early-stage investor in the company’s lifecycle. (A pro-rata is the option to retain original ownership in a startup in subsequent financing rounds, which requires an additional cash investment. For more info on pro-rata, this is an excellent resource.)

From the VC perspective, there are two competing forces at work: a fund must continue adding money to an investment to preserve its ownership percentage, but concentrating on one investment means there is less money to bet on other potential high-growth startups.

To bring it back to the whaling metaphor: do you continue directing more and more voyages to a particular location knowing that it has been successful, or do you allocate those resources to explore untapped locations with a potentially larger prize?

Elizabeth Yin published a twitter thread arguing that it’s not worth it for early-stage investors to worry about ownership percentage here, that drew its fair share of debate:

Not all funds target a specific ownership percentage. Some venture funds like Clocktower Technology Ventures invest a fixed check size for each of their investments at the seed stage.

We asked Ben Savage, the General Partner at Clocktower Technology Ventures, how he approaches ownership percentage, pro-rata rights, and his thesis on portfolio management and check size:

“We try to size our investments wielding a bit of classic portfolio optimization math. If you have a fixed amount of money to invest in a portfolio (i.e., a VC fund), and you don’t know the expected return, risk and correlation of the underlying investments (which we think is generally true about seed stage VC bets) then the optimal approach is to size your portfolio using a 1/N calculation. So we think of roughly how many investments we expect our fund to make at seed (the “N”) and then size them equally. In this way we don’t vary our investment size based on our conviction levels, out of respect for the significant uncertainties of seed-stage venture risk, nor do we vary it based on valuation—if you have to own a fixed size of a company you’re quite literally investing more money in more expensive deals.”

As a startup entrpreneur, it's essential that you have a good understanding of the VC mindset and their goals. This will give you more context while fundraising and allow you to put yourself in the shoes of the people betting on your success.

Summary

- The term “venture capital” was coined in the financing of whaling expeditions

- VC is a high risk, high return business, just like the whaling expeditions of yesteryear

- VC’s make money in two ways: management fees and carried interest

- Measuring VC performance is an art and a science, like measuring a company’s valuation

- Most VC funds use the “2 and 20” model to fund the firm’s operations and earn carry on profitable investments

- VC ownership targets change depending on the size of the fund and their portfolio management thesis

RELATED

Venture Debt Financing For Startups

Venture debt financing can give your company access to working capital, while minimizing share dilution. Learn all you need to know about it as a founder.

Written by James Hottensen

James joined Capbase after working at Great Oaks Venture Capital in New York where he worked on various fin-tech and consumer investments as an Associate, including Capbase and Golden. He previously worked at Tentrr, a Series A startup in New York, leading Strategy and Partnerships.

Related

What is a Startup Syndicate and How Does it Work?

Learn how startup syndicates work, who creates startup syndicates, and the pros and cons of raising funds through startup syndicates.

by Michał Kowalewski • 10 min read

by Michał Kowalewski • 10 min readHow Do Venture Capitalists Make Investment Choices?

Before you seek VC funding for your startup, you should know what venture capital firms are looking for when deciding to invest in a startup.

by James Hottensen • 7 min read

by James Hottensen • 7 min readHow to Use Twitter Effectively to Raise Money For Your Startup

Twitter is an amazing platform for fundraising outreach when used effectively. Read this article and learn how to connect with investors on Twitter

by James Hottensen • 7 min read

by James Hottensen • 7 min read

by

by

by

by